There is a concept in chemistry known as activation energy.

Here’s how it works:

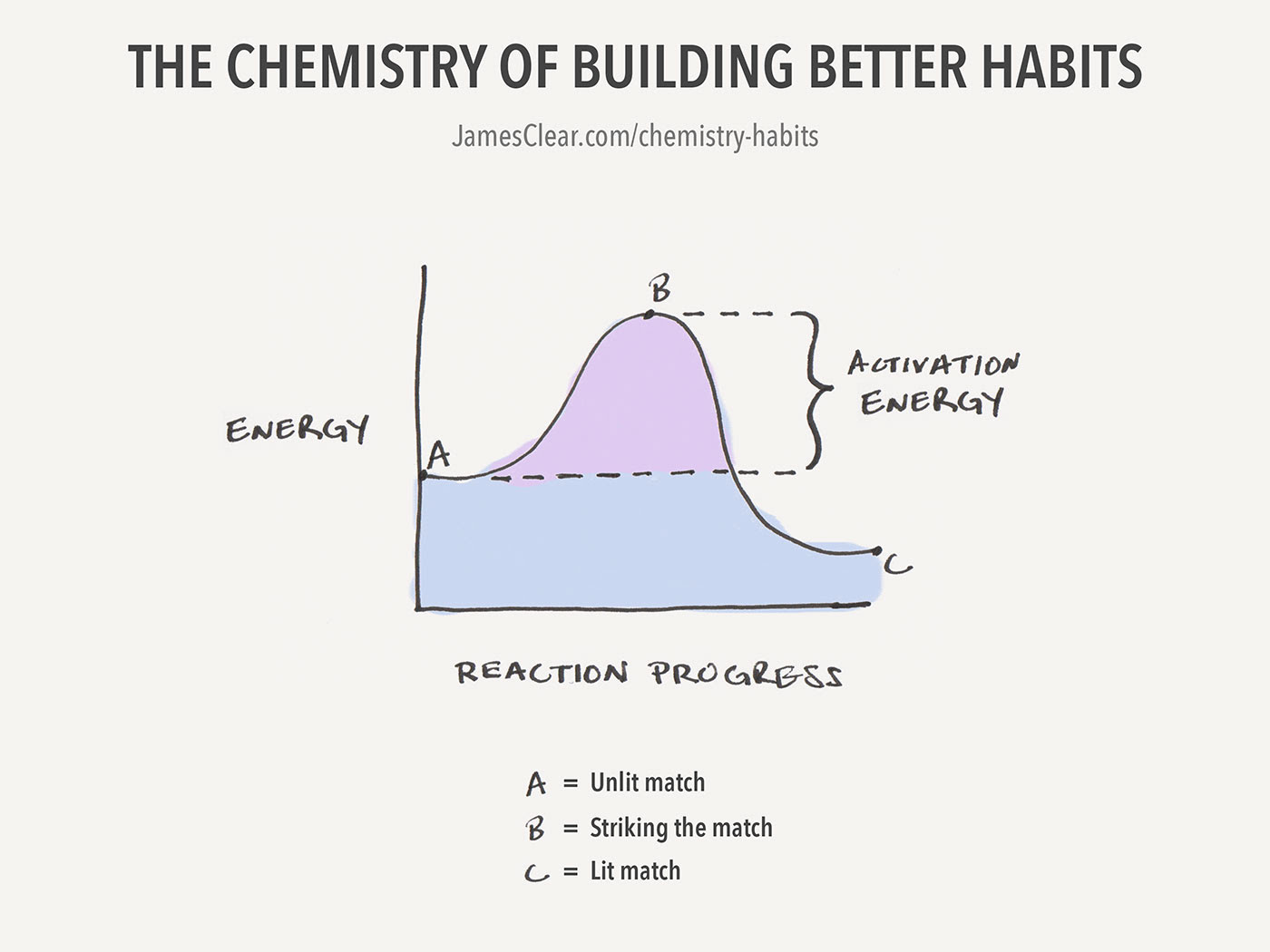

Activation energy is the minimum amount of

energy that must be available for a chemical reaction to occur. Let’s

say you are holding a match and that you gently touch it to the striking

strip on the side

of the match box. Nothing will happen because the

energy needed to activate a chemical reaction and spark a fire is not

present.

However, if you strike the match against the

strip with some force, then you create the friction and heat required to

light the match on fire. The energy you added by striking the match was

enough to reach the activation energy threshold and start the reaction.

Chemistry textbooks often explain activation energy with a chart like this:

It’s sort of like rolling a boulder up a hill.

You have to add some extra energy to the equation to push the boulder to

the top. Once you’ve reached the peak, however, the boulder will roll

the rest of the way by itself. Similarly, chemical reactions require

additional energy to get started and then proceed the rest of the way.

Alright, so activation energy is involved in

chemical reactions all around us, but how is this useful and practical

for our everyday lives?

The Activation Energy of New Habits

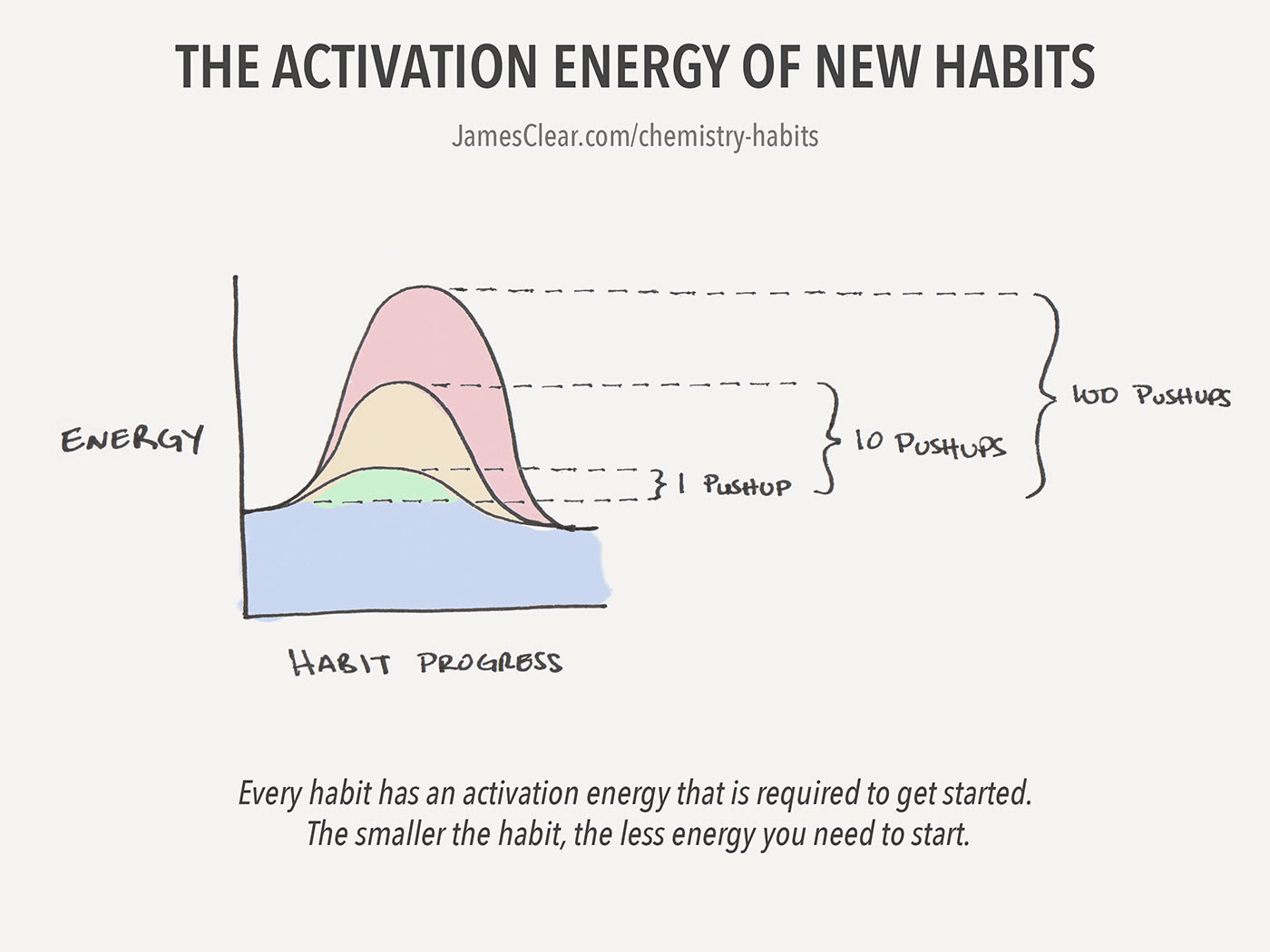

Similar to how every chemical reaction has an

activation energy, we can think of every habit or behavior as having an

activation energy as well.

This is just a metaphor of course, but no matter

what habit you are trying to build there is a certain amount of effort

required to start the habit. In chemistry, the more difficult it is for a

chemical reaction to occur, the bigger the activation energy. For

habits, it’s the same story. The more difficult or complex a behavior,

the higher the activation energy required to start it.

For example, sticking to the habit of doing 1

pushup per day requires very little energy to get started. Meanwhile,

doing 100 pushups per day is a habit with a much higher activation

energy. It’s going to take more motivation, energy, and grit to start

complex habits day after day.

The Disconnect Between Goals and Habits

Here’s a common problem that I’ve experienced when trying to build new habits:

It can be really easy to get motivated and hyped

up about a big goal that you want to achieve. This big goal leads you

to think that you need to revitalize and change your life with a new set

of ambitious habits. In short, you get stuck dreaming about life-changing outcomes rather than making lifestyle improvements.

The problem is that big goals often require big

activation energies. In the beginning you might be able to find the

energy to get started each day because you’re motivated and excited

about your new goal, but pretty soon (often within a few weeks) that

motivation starts to fade and suddenly you’re lacking the energy you

need to activate your habit each day.

This is lesson one: Smaller

habits require smaller activation energies and that makes them more

sustainable. The bigger the activation energy is for your habit, the

more difficult it will be to remain consistent over the long-run. When

you require a lot of energy to get started there are bound to be days

when starting never happens.

Finding a Catalyst for Your Habits

Everyone is on the lookout for tactics and hacks

that can make success easier. Chemists are no different. When it comes

to dealing with chemical reactions, the one trick chemists have up their

sleeves is to use what is known as a catalyst.

A catalyst is a substance that speeds up a

chemical reaction. Basically, a catalyst lowers the activation energy

and makes it easier for a reaction to occur. The catalyst is not

consumed by the reaction itself. It’s just there to make the reaction

happen faster.

Here’s a visual example:

When it comes to building better habits, you also have a catalyst that you can use:

Your environment.

The most powerful catalyst for building new habits is environment design (what some researchers call choice architecture).

The idea is simple: the environments where we live and work influence

our behaviors, so how can we structure those environments to make the

good habits more likely and the bad habits more difficult?

Here is an example of how your environment can act as a catalyst for your habits:

Imagine you are trying to build the habit of

writing for 15 minutes each evening after work. A noisy environment with

loud roommates, rambunctious children, or constant television noise in

the background will require a high activation energy to stick with your

habit. With so many distractions, it’s likely that you’ll fall off track

with your writing habit at some point. Meanwhile, if you stepped into a

quiet writing environment—like a desk at the local library—your

surroundings suddenly become a catalyst for your behavior and make it

easier for the habit to proceed.

Your environment can catalyze your habits in big

and small ways. If you set your running shoes and workout clothes out

the night before, you just lowered the activation energy required to go

running the next morning. If you hire a meal service to deliver low

calorie meals to your door each week, you significantly lowered the

activation energy required to lose weight. If you unplug your television

and hide it in the closet, you just lowered the activation energy

required to watch less tv.

This is lesson two: The right environment is like a catalyst for your habits and it lowers the activation energy required to start a good habit.

The Intermediate States of Human Behavior

Chemical reactions often have a reaction

intermediate, which is like an in-between step that occurs before you

can get to the final product. So, rather than going straight from A to

B, you go from A to X to B. An intermediate step needs to occur before

we go from starting to finishing.

There are all sorts of intermediate steps with habits as well.

Say you want to build the habit of working out.

Well, this could involve intermediate steps like paying a gym

membership, packing your gym bag in the morning, driving to the gym

after work, exercising in front of other people, and so on.

Here’s the important part:

Each intermediate step has its own activation

energy. When you’re struggling to stick with a new habit it can be

important to examine each link in the chain and figure out which one is

your sticking point. Put another way, which step has the activation

energy that prevents the habit from happening?

Some intermediate steps might be easy for you.

To continue our fitness example from above, you might not care about

paying for a gym membership or packing your gym bag in the morning.

However, you may find that driving to the gym after work is frustrating

because you end up hitting more rush hour traffic. Or you may discover

that you don’t enjoy working out in public with strangers.

Developing solutions that remove the

intermediate steps and lower the overall activation energy required to

perform your habit can increase your consistency in the long-run. For

example, perhaps going to the gym in the morning would allow you to

avoid rush hour traffic. Or maybe starting a home workout routine would

be best since you could skip the traffic and avoid exercising in public.

Without these two barriers, the two intermediate steps that were

causing friction with your habit, it will be much easier to follow

through.

This is the lesson three: Examine

your habits closely and see if you can eliminate the intermediate steps

with the highest activation energy (i.e. the biggest sticking points).

The Chemistry of Building Better Habits

The fundamental principles of chemistry reveal some helpful strategies that we can use to build better habits.

- Every habit has an activation energy that is required to get started. The smaller the habit, the less energy you need to start.

- Catalysts lower the activation energy required to start a new habit. Optimizing your environment is the best way to do this in the real world. In the right environment, every habit is easier.

- Even simple habits often have intermediate steps. Eliminate the intermediate steps with the highest activation energy and your habits will be easier to accomplish.

And that’s the chemistry of building better habits.

Share on Facebook | Share on LinkedIn | Share on Twitter

James Clear is

a writer and researcher on behavioral psychology, habit formation, and

performance improvement. His work is read by over 500,000 people each

month and he is frequently a keynote speaker

at top-tier organizations like Stanford University and Google. He

believes in developing a diversity of knowledge and maintains a public

reading list of the best books to read across a wide range of disciplines.

No comments:

Post a Comment